[By Glynnis Stevenson]

No monument stands over Babi Yar.

A drop sheer as a crude gravestone.

I am afraid.

Today I am as old in years

as all the Jewish people.

Now I seem to be

a Jew.

Here I plod through ancient Egypt.

Here I perish crucified on the cross,

and to this day I bear the scars of nails.

I seem to be

Dreyfus.

The Philistine

is both informer and judge.

I am behind bars.

Beset on every side.

Hounded,

spat on,

slandered.

Squealing, dainty ladies in flounced Brussels lace

stick their parasols into my face.

I seem to be then

a young boy in Byelostok.

Blood runs, spilling over the floors.

The barroom rabble-rousers

give off a stench of vodka and onion.

A boot kicks me aside, helpless.

In vain I plead with these pogrom bullies.

While they jeer and shout,

‘Beat the Yids. Save Russia!’

Some grain-marketer beats up my mother

O my Russian people!

I know

you

are international to the core.

But those with unclean hands

have often made a jingle of your purest name.

I know the goodness of my land.

How vile these antisemites—

without a qualm

they pompously called themselves

the Union of the Russian People!

I seem to be

Anne Frank

transparent

as a branch in April.

And I love.

And have no need of phrases.

My need

is that we gaze into each other.

How little we can see

or smell!

We are denied the leaves,

we are denied the sky.

Yet we can do so much—

tenderly

embrace each other in a darkened room.

They’re coming here?

Be not afraid. Those are the booming

sounds of spring:

spring is coming here.

Come then to me.

Quick, give me your lips.

Are they smashing down the door?

No, it’s the ice breaking . . .

The wild grasses rustle over Babi Yar.

The trees look ominous,

like judges.

Here all things scream silently,

and, baring my head,

slowly I feel myself

turning grey.

And I myself

am one massive, soundless scream

above the thousand thousand buried here.

I am

each old man

here shot dead.

I am

every child

here shot dead.

Nothing in me

shall ever forget!

The ‘Internationale,’ let it

thunder

when the last antisemite on earth

is buried for ever.

In my blood there is no Jewish blood.

In their callous rage, all antisemites

must hate me now as a Jew.

For that reason

I am a true Russian!

–“Babi Yar” (1961), Yevgeny Yevtushenko

Commemorating Babi Yar

The Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko opens his most famous work, “Babi Yar,” with the phrase “No monument stands over Babi Yar.” Until 1976, the Ukrainian ravine stood unmarked. There was no immense memorial to the victims of Nazi savagery to mark their final resting place. The most infamous massacre at the site occurred from September 29th to 30th, 1941. Babi Yar is widely considered to be “the largest single massacre in the history of the Holocaust” (Lower). In one operation, 33, 771 Jews were murdered, and the Einsatzgruppen continued to use the site to annihilate Soviet prisoners of war, communists, Roma, and Ukrainian civilians (Magocsi, 633). Upwards of 100,000 people lost their lives at Babi Yar ravine, but for thirty-five years, there was no statue built in remembrance of those swallowed by the earth.

As early as 1943, Babi Yar ravine was the subject of political debate. Unwilling to emphasize the suffering of Jewish victims, the Soviet government announced that the Nazi regime had committed crimes against the Soviet people as a whole. Many attempts were made to commemorate the Jewish victims with a monument, but all attempts were rejected by the Soviet high command. In 1976, a monument was erected for the Soviet victims of Nazi genocide, but it failed to identify the specific ethnic minorities who perished at the site. Only after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 was a Jewish memorial built at Babi Yar. A year later, a wooden cross was built at the site in honor of the Ukrainian civilians murdered at the ravine. These disparate monuments only serve to remind us of the deep divisions between different groups that persist into the modern day. Overcoming these divides, Yevtushenko’s poem and Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony serve together as a memorial to all victims of genocide and persecution.

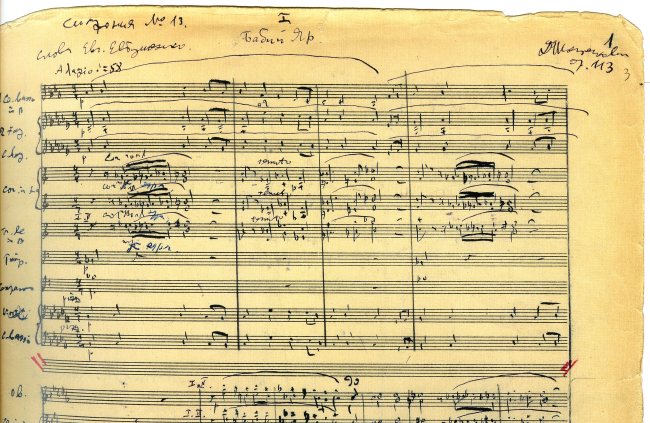

In “Babi Yar”, written in 1961, Yevtushenko openly denounced Soviet anti-Semitism. Soviet policy normally emphasized Nazi atrocities against all Soviet citizens and avoided any mention of the Nazis’ methodical annihilation of Jews. The poem was published in the weekly cultural newspaper, Literaturnaya Gazeta (Literaturnaya Gazeta, 19 September 1961), during Khrushchev’s cultural “Thaw”, and soon became a popular emblem of resistance to the Soviet regime. It was widely circulated in clandestine newspapers and magazines as well. After the stifling censorship of the Stalin years, Yevtushenko’s denunciation of the Soviet regime’s anti-Semitism gave hope to a younger generation that feared the state less than their parents did and who were passionate about political change. Yevtushenko’s friend Dmitri Shostakovich was even more active in his denunciations of the Soviet regime. As Stalin’s government dismissed Jewish musicians from their jobs, Shostakovich, who took much of his inspiration from Jewish folk music, was one of a handful of musicians to sign petitions to garner financial support for his fired colleagues. He wrote his vocal cycle, From Jewish Folk Poetry, in 1948, in response to Stalinist persecution of Jews, but did not dare to premiere it until 1955. Unable to showcase his controversial works publically, Shostakovich felt increasingly alienated and, consequently, he identified with the Jews, whom he saw as an eternal symbol of persecution. Upon reading “Babi Yar”, Shostakovich felt compelled to help Yevtushenko’s words resonate with a wider audience and composed his five-movement Thirteenth Symphony in B Flat Minor with a haunting lament set to the words of “Babi Yar”.

Written for bass solo, male chorus, and orchestra, Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony, more popularly known as “Babi Yar”, is a commemorative piece for all victims of persecution and genocide. The Adagio (“slow and stately”) tempo helps to enrich the sonorous intensity of the bass solo. With the exception of a rich bass solo, Yevtushenko’s words are mostly sung in unison, adding to the feeling of solidarity in the face of death. Though some argue that unison singing is musically simplistic, I believe that in this case it serves to make the poem’s message more resonant. Shostakovich does not allow the words to become bogged down by bombast; every word rings clear over the sounds of the orchestra. While Yevtushenko’s poem alone only resonated within the urban centers of the Soviet Union, the premiere of Shostakovich’s latest composition was highly anticipated on an international scale. No one in the Soviet Union had dared for a long time to cry out so openly against Soviet anti-Semitism. Khrushchev openly despised Yevtushenko’s poem and setting it to music brought Shostakovich into direct confrontation with the authorities. Fearing the international appeal of a song against tyranny, the Soviet authorities attempted to prevent the premiere. Pressure from the government persuaded Yevgeny Mravinsky, Shostakovich’s most constant interpreter and preferred conductor, to pass on performing at the premiere. Shostakovich felt deeply betrayed by his friend, who had dared to perform Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, a direct rejection of Stalin’s preferred classical sound, at the height of the Stalinist purges in 1937. Mravinsky and Shostakovich had come through the purges together, but Mravinsky was not willing to risk the wrath of the Soviet government to conduct Shostavich’s most dangerous work yet. Despite pressure from the authorities, Kirill Kondrashin, a longtime friend of Shostakovich’s, stepped in as conductor.

On the night of the premiere, December 18, 1962, both the Soviet audience and the foreign media were focused on the first movement. Though “Babi Yar” refers to a specific Nazi atrocity, the majority of the piece is decidedly anti-Stalinist. The fourth movement, “Fears”, was written specifically for Shostakovich by Yevtushenko and elicits the fear of denunciation many felt living under Stalin’s regime: “Secret fear of someone’s denunciation/Secret fear of a knock on the door” (Volkov, 274). A victim of blacklists and bans, these words elicit Shostakovich’s own fears as well as Yevtushenko’s. Mostly ignorant of Stalin’s persecution of Jews, the international community praised the piece as a denunciation of Nazi anti-Semistism and genocide. The premiere of the Thirteenth Symphony received a standing ovation and acclaim from the foreign press, but Shostakovich was disheartened. He complained that musicologists were interpreting his work incorrectly in “moving the emphasis to Nazi Germany” (Volkov, 275). He was even more upset that the Soviet government did not even bother to blacklist his work after the success of the premiere; his passion for social change inspired his work, without the authorities harassing him, he had little to struggle against.

Today there are many memorials to those who found their final resting place at Babi Yar, but only one overcomes petty ethnic divides to give a voice to all victims of persecution and genocide. Yevtushenko did not simply identify with Jews. He ends “Babi Yar” with a clarion call: “I am a Russian!”His denunciation of Stalinism does not diminish in anyway his love for his country. “Babi Yar”, both the poem and the subsequent symphony, is a memorial that overcomes all petty divisions and commemorates all who have been victims of persecution.

________________________________________________________________

Works Consulted:

- Shostakovich in Context. Edited by Rosamund Bartlett (Oxford University Press, 2000).

- The Cambridge Companion to Shostakovich. Edited by Pauline Fairclough and David Fanning (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- Shostakovich Studies. Edited by David Fanning (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- Wendy Morgan Lower, “From Berlin to Babi Yar. The Nazi War against the Jews, 1941-1944,”Journal of Religion and Society, Volume 9 (2007).

- Brian Morton, Shostakovich: His Life and Music (London: Haus Publishing Limited, 2006).

- Solomon Volkov, Shostakovich and Stalin (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., 2004).

- Yevtushenko, Yevgeny. “Babi Yar.” PBS. http://www.pbs.org/auschwitz/learning/guides/reading1.4.pdf.