[Chelsea Bracci]

The Nukus Museum of Art is a site of memory of repression under the Soviet repression which is being censored itself. The Nukus Museum remembers Soviet and Russian art which was being censored, but is designed to preserve Uzbek art, and in doing so highlights a period in history the Uzbekistan government would rather lay to rest. This museum is facing the same fate as the art it houses, unwittingly remembering and living the repression and censorship. However this time, museum and the precious collection of art which lives inside it, cannot be secreted away in the night and hidden until it is safe.

Igor Savitsky , painter, collector, and archeologist, was born in Kiev Russia in 1915. Savitsky first experienced Central Asia during World War II when he was evacuated to Samarkand. During his first excursion into the Central Asia he became fascinated with the culture of the region and returned in 1950 to Karakalpakstan as the artist for the Khorezm Archeological and Ethnographic Expedition. Beyond his artistic duties to the expedition Savitsky set out to explore the area including the villages where he came across local folk art (Nukus Museum). The expedition was completed in 1957 but Savitsky decided to stay behind, giving up his life in Moscow, and moved to Nukus and took on a position at the Karakalpak branch of the Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences. Savitsky began collecting carpets, costumes, jewelry, and other objects from the local communities as well as drawings and paintings of artists linked to Central Asia. These artists included those from the Uzbek School and Russian avant-garde artists who were being censored during the late 1950’s and early 1960’s under the Soviet regime (Pope & Georgiev)

, painter, collector, and archeologist, was born in Kiev Russia in 1915. Savitsky first experienced Central Asia during World War II when he was evacuated to Samarkand. During his first excursion into the Central Asia he became fascinated with the culture of the region and returned in 1950 to Karakalpakstan as the artist for the Khorezm Archeological and Ethnographic Expedition. Beyond his artistic duties to the expedition Savitsky set out to explore the area including the villages where he came across local folk art (Nukus Museum). The expedition was completed in 1957 but Savitsky decided to stay behind, giving up his life in Moscow, and moved to Nukus and took on a position at the Karakalpak branch of the Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences. Savitsky began collecting carpets, costumes, jewelry, and other objects from the local communities as well as drawings and paintings of artists linked to Central Asia. These artists included those from the Uzbek School and Russian avant-garde artists who were being censored during the late 1950’s and early 1960’s under the Soviet regime (Pope & Georgiev)

Early in the twentieth century, many artists were attracted to Central Asia, resulting in a virtual artistic colonization of the region in the decade following the revolution. Savitsky collected works from the Central Asian art school which included such artists as Isupov, Kramarenko, Ulyanov, and Voloshin. Within this school was the Uzbek school which included artists such as Volkov, Kurzin, Karakhan, Tansykbaev, Ufimtsey, and Robert Falk, whom he had met during his first visit to Central Asia (Babanzarova).

Volkov, who is considered to be the father of the Uzbek school of art, thought of the art of Central Asia, in the words of one scholar, as “built on a foundation of decorative design and ‘primitivism’- by which he meant decorative applied arts with their specific quality of depicting the world by simplifying and geometrically stylizing real forms” (Babanzarova).

While many artists also expressed a tendency towards the use of primitivism as a means of imagining oriental themes, others drew from the spectrum of artistic styles. Artists such as Benkov chose to explore Impressionism which was developed in France during the 19th century and is characterized by loose brush work, an intense interest in color pairings, and scenes from everyday life. Volkov also experimented with Cubo-Futurism which developed in Russia ca. 1910 and was a blend of French Cubism, Italian Futurism, and primitivism. Cubo- futurism focused on bold colors, emphasized movement and action, and the compositions could include random letters or words. Fauvism, Expressionism, Symbolism, and Neoclassicism with Romanticism proved to be powerful influencing styles on the work of the Uzbek school as well. The blend of European modernism, which was being imported by foreign artists, and the artistic traditions of the region led to the creation of a distinct Uzbek School style (Babanzarova).

While working to support the local artistic culture, Savitsky became concerned with the censorship and persecution of Russian avant-garde artists. The Russian avant-garde movement is the collective term for the artistic movement of the first half of the 20th century that included thousands of artists and dozens of different styles. While not a cohesive stylistic movement, the Russian avant-garde movement was united by an artistic desire to break from the past and fight for the right of self-expression. It is the search for new means of expression in changing times, rather than technique, that united these artists into a movement (Kofyan).

Artists, along with the rest of the Intelligentsia across Russia, were persecuted as dissidents and became victims of the Great Terror of the 1930s (Library of Congress). Many artists chose to leave Russia in order to escape the persecution, but those who stayed and refused to waver in their vision faced the possibility of being sent to mental hospitals, the gulag, or executed. One such artist who was persecuted was Yevgeny Lysenko. Lysenko refused to waver in his artistic vision and after the public exhibition of his blue bull painting, Fascism Is Advancing,which had been labeled anti-Soviet, he was sent to a mental hospital. Savitsky risked the same fate of being denounced and labeled an “enemy of the people” in order to save thousands of Russian avant-garde and post avant-garde paintings (Pope & Georgiev).

Savitsky began to rescue works of art by pretending to buy state approved art. He traveled back and forth from Moscow by train saving thousands of canvases by artists who had been branded formalists. He was able to amass funds to pay for the art at times from the very authorities who were banning it or by writing notes promising repayment in the next 10 to 12 years. Despite the difficulty and the danger, Savitsky successfully rescued 40,000 works of art from destruction across Russia in an unprecedentedly short period of time. Savitsky was able to convince the local authorities in Nukus that there needed to be an art museum to house this growing collection of Russian avant-garde and Uzbek works of art along with the objects he had been collecting from the region. Following the establishment of the museum in 1966, Savitsky was appointed the curator of the Savitsky Karalkapakstan Art Museum. The museum houses the second largest collection of Russian avant-garde works, second only to the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, and contains close to 90,000 items including graphics, paintings and sculptures, as well as thousands of artifacts ranging from the antiquities of Khorezm’s ancient civilization to the works of contemporary Uzbek and Karakalpak artists. The Nukus Museum of art is beginning to be recognized as one of the most important art institutions in Asia (Nukus Museum).

Not until 1991, when Uzbekistan became independent, did Nukus cease to be a remote ‘closed’ city of the Soviet Union and become accessible to the outside world. Following the fall of the Soviet Union the Nukus Museum became accessible not only to art experts but to journalists, diplomats and businessmen. Stories about Savitsky and his museum became international news and brought recognition and acclaim to the Nukus museum which housed the ground-breaking collection (Nukus Museum). However one of the most remarkable collections of 20th century Russian art is still in as much danger as when Savitsky first began building the collection. The Nukus collection is worth millions and has become a target of Islamic fundamentalists, corrupt bureaucrats, and art profiteers. If the difficult political and economic conditions continue in Central Asia, the Savitsky Collection could cease to exist (Pope & Georgiev).

Since the founding of the museum there have been appeals for funds and aid in order to keep the museum open. Friends of Nukus Museum (FoNM) was initially set up as an informal group during the early 1990’s and was established as a non-governmental organization in 2001. It functioned as an international network of supporters until 2007 when it was reestablished as the Friends of Nukus Museum Foundation. Registered as a Dutch charity, the FoNM works directly with the Museum’s Director, Marinika M. Babanazarova, on a variety of issues. From working with donors to organizing exhibitions abroad, this network of supporters is dedicated to keeping the museum open despite lack of funding and political pressures (Nukus Museum).

While there is no clear explanation for the governmental suppression of the Nukus Museum, the political tension may be a reflection of lasting ambivalence towards Russia. Since gaining independence in 1991, the Uzbekistan government has mounted a campaign promoting native forms of art by ethnic Uzbeks. The Savitsky collection, which contains pieces created by ethnic Russians as well as pieces featuring Russian influenced styles, did not conform to this national narrative of art (Pope & Georgiev). The Uzbek Ministry of Culture has refused international invitations to display works from the collection since the first exhibitions that took place in Germany and France in the early 1990’s. According the museum’s director, the only exception that has been made to this policy is the three paintings on view in the Netherlands (Berry).

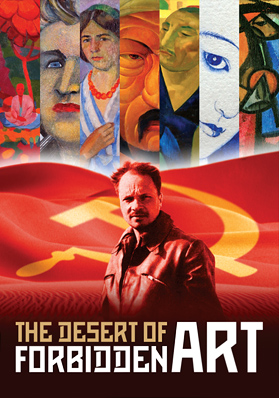

International attention was brought to the tension between the Uzbek government and the Nukus museum in 2011 with the release of the documentary The Desert of Forbidden Art (directed by Amanda Pope and Tchavdar Georgiev). The documentary tells the story of “an amazing art collection, created single-handedly by one penniless man, in the desert, a poor region, in an Islamic country suspicious of art created by their former colonizers” (Pope & Georgiev). The government became increasingly hostile towards the Nukus museum after the release of the PBS documentary. Over the course of 2011 the museum’s staff was subject to 15 government audits which required them to repeatedly explain their international travels and the nature of their relationships with foreign contacts. In 2011 Uzbek officials abruptly gave the Nukus Museum 48 hours to evacuate one of two exhibition buildings. Staff members were forced to stack hundreds of fragile pieces of art and quickly move them into the other building where they had to be stacked on the floor. Due to the cut in exhibition space, 2,000 works could no longer be viewed. In the days following the loss of the second exhibition building, the museum’s director Marinika M. Babanazarova, who had been with the museum for 27 years, was not permitted to travel to the United States for the screening of the documentary. Director Babanazarova explains the situation: “It’s a great satisfaction that we are getting international recognition. On the other hand, it complicates our lives, to be honest” (Berry).

The museum continues to be in limbo trying to find a balance between international recognition and political pressure from the Uzbek government. The Savitsky Karalkapakstan Art Museum houses a collection that has shaken the foundations of art history of the Soviet era and stands as a stark refutation of the Socialist Realist school of art. Savitsky stated “I like to think of our museum as a keeper of the artists’ souls … Their works are the physical expression of a collective vision that could not be destroyed” (Pope & Georgiev). However it is unclear how long this collection of art will evade destruction. From the Soviet Union to the Uzbek government, since the first canvas smuggled out of Moscow, the Savitsky collection has been under constant threat. Today Savitsky’s museum is struggling to stay viable under pressure from private buyers, Islamic extremists, and the Uzbek government. If the art housed within this cramped museum space does not receive proper restoration soon, this physical evidence of an entire artistic school will soon literally dissolve into the desert.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Work Cited:

- Karakalpakstan State Museum of Art: http://www.savitskycollection.org/pages/Karakalpak_History.html

- The Desert of Forbidden Art, Dir. Amanda Pope and Tchavdar Georgiev(PBS, 2011).http://desertofforbiddenart.com/about

- Marinika Babanzarova, The Uzbek School (Steppe, Winter 2007-2008)

- Library of Congress Soviet Archives Online Exhibit: Attacks on Intelligentsia (Library of Congress). http://www.ibiblio.org/expo/soviet.exhibit/attack.html

- Vera Kofyan, Introduction For Those New To Russian Avant-garde (Russian Avant-garde Gallery, 2012). http://www.russianavantgard.com/introduction-for-those-new-to-russian-avantgarde-t-2.html

- Ellen Berry, ‘Decadent’ Russian Art, Still Under the Boot’s Shadow (New York Times, 2011). http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/08/arts/design/desert-of-forbidden-art-igor-savitsky-collection-in-nukus.html?pagewanted=all